research

I write about skepticism in contemporary philosophy and the modern period, especially in Hume and Kant.

Here is my CV.

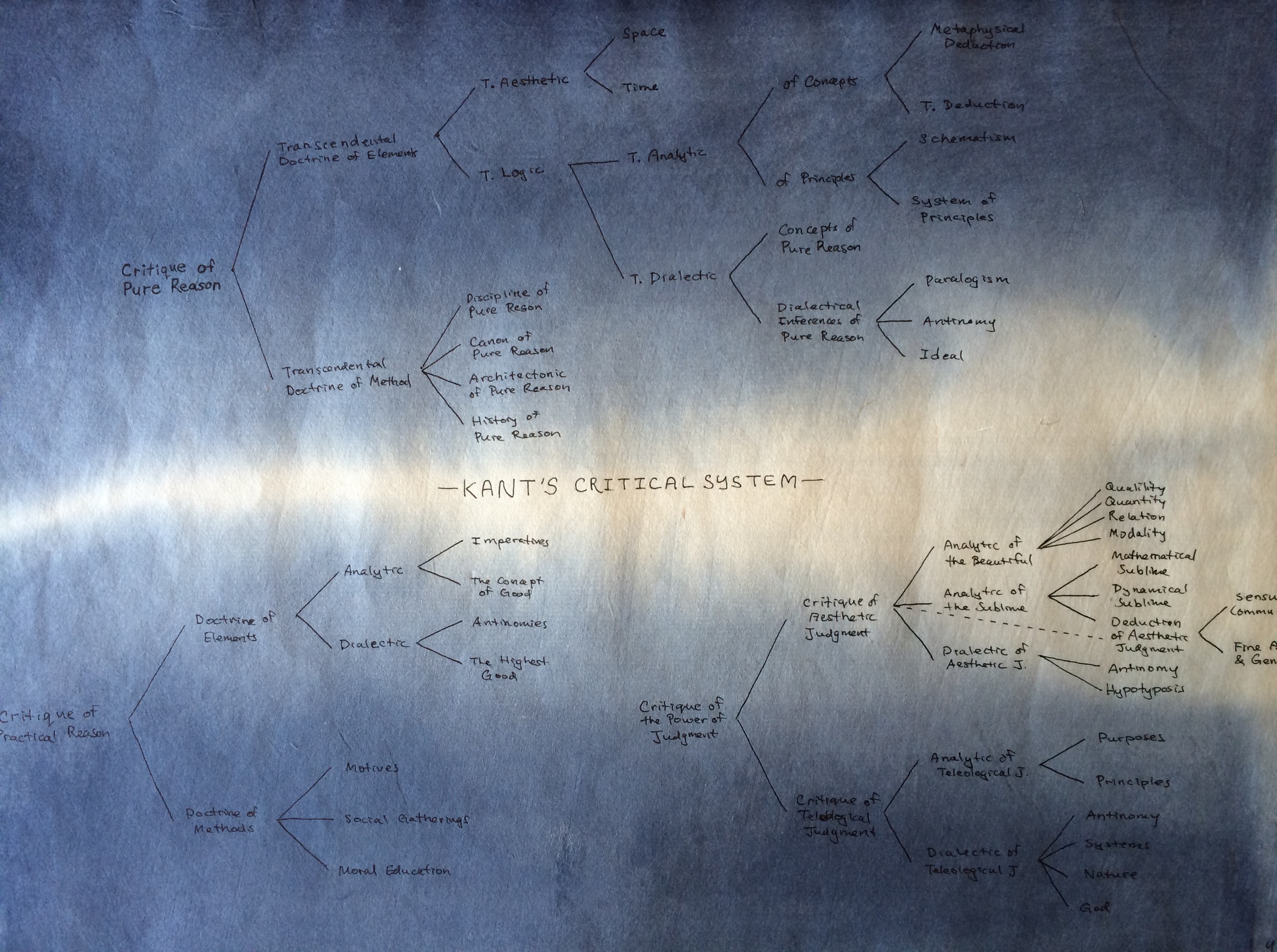

Kant's Critical System, painted and sketched by me in 2014

INTERESTS

My main areas of interest are epistemology and the history of modern philosophy. In both cases, my primary topic is skepticism, the view or feeling that we know very little. My research addresses questions like: How can we talk to people who are deeply and radically skeptical? What kinds of considerations or arguments could lead skeptics to change their mind? Where does skepticism come from, and in what ways can it be healthy or harmful? I treat these as live philosophical questions. But my approach is informed by historical treatments of skepticism, especially those of Hume and Kant.

I am also interested in the philosophy of perception, philosophy of action, moral psychology, Hellenistic philosophy, early modern feminism, the history of medicine, existentialism, and Zen.

ARTICLES

“Layered Irony in Sor Juana and Hume’s Compositions on Skepticism,” forthcoming in Archiv für Geschichte der Philosophie.

I compare a 1689 ballad by the Mexican Hieronymite nun Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz with a 1742 essay by David Hume. I argue that each composition conveys competing messages: Their surface-level skepticism about the value of learning is countered by ironic optimism, leading finally to a more balanced position. Both composition's use of a literary device called ‘layered irony’ helps them play philosophy’s traditional role as a kind of therapy.

“Kant’s Offer to the Skeptical Empiricist” (2024), Journal of the History of Philosophy 62 (3):421–47.

I argue that Kant tries to change the mind of a skeptical empiricist by offering, rather than compelling acceptance of, an alternative conception of our knowledge, and that his offer can appeal because of an instability inherent to the skeptic’s position. [preprint]

“Hume’s Skeptical Philosophy and the Moderation of Pride” (2024), Philosophy and Phenomenological Research 108 (3): 621–36.

Hume states that skeptical philosophy is to have desirable effects on our doxastic dispositions by first diminishing our pride. I give a Humean reconstruction of the mechanisms involved: Skeptical philosophy diminishes pride by removing our tendency to view ourselves as better than others. And diminishing excessive pride removes a cause of pride-driven, doxastic reinforcement loops. [New Works in Philosophy blog version]

“The Dissatisfied Skeptic in Kant’s Discipline of Pure Reason” (2023), Journal of Transcendental Philosophy 4 (2): 157–77.

Kant’s longest and most revealing discussion of skepticism in the first Critique appears in the Discipline of Pure Reason. I explain what Kant’s criticism is and why it appears where it does. Though skepticism produces doubt concerning reason’s attempts at speculative metaphysics, it does not produce knowledge of their impossibility; it thus fails to discipline those attempts.

“Hume’s Real Riches” (2022), History of Philosophy Quarterly 39 (1): 45–57.

Why does Hume call a cheerful temperament “real riches”? I argue that he views it under two aspects: social mirth and steadfastness against misfortunes. The second aspect is of special interest to Hume in that it safeguards the other virtues. And the first aspect explains how cheerfulness differs from the classical, heroic virtue of Stoic tranquility.

“The Humors in Hume’s Skepticism” (2021), Ergo: An Open Access Journal of Philosophy 7 (30), 789–824.

Interpreters have struggled to explain the succession of stages in Hume’s recovery from melancholy in the conclusion to Book I of the Treatise. I argue that Hume’s repeated invocation of the four humors of ancient medicine explains the succession, and sheds a new light on the role of skepticism in his theory of human nature. [Ergo blog version]

“Does Perceptual Psychology Rule Out Disjunctivism in the Theory of Perception?” (2021), Synthese 198 (8): 7025–47

Against Tyler Burge, I argue that the science of perceptual psychology holds no commitments that are inconsistent with epistemic disjunctivism, the view that genuine perceptions and misperceptions differ in epistemic kind.

REVIEWS AND PROCEEDINGS

Review of Abraham Anderson’s The Skeptical Roots of Critique: Hume’s Attack on Theology and the Origin of Kant’s Antinomy, forthcoming in Journal of the History of Philosophy.

Review of Gabriele Gava’s Kant’s Critique of Pure Reason and the Method of Metaphysics (2024), Journal of Transcendental Philosophy 5 (2–3): 145–50.

Review of Nathan I. Sasser’s Hume and the Demands of Philosophy: Science, Skepticism, and Moderation (2023), Journal of Scottish Philosophy 21 (3): 313–17.

Review of Michael Bergmann’s Radical Skepticism and Epistemic Intuition (2023), Notre Dame Philosophical Reviews.

Review of Peter S. Fosl’s Hume’s Scepticism: Pyrrhonian and Academic (2022), Hume Studies 46 (1): 171–74.

“How Kant Thought He Could Reach Hume,” in The Court of Reason: Proceedings of the 13th International Kant Congress (2021), Ed. Camilla Serck-Hanssen & Beatrix Himmelmann, Berlin: Walter de Gruyter, Vol. 2: 717–26.

“Discussion of John McDowell’s ‘Perceptual Experience and Empirical Rationality’” (2018), Analytic Philosophy 59 (1): 102.

“Discussion of Anil Gupta’s ‘Outline of an Account of Experience’” (2018), Analytic Philosophy 59 (1): 80–81.

DISSERTATION

Talking to Skeptics

Committee: John McDowell (chair), Stephen Engstrom, James Shaw, Karl Schafer (UT Austin)

Skeptics argue that we can know almost nothing at all. In doing so, they threaten our understanding of ourselves and the world we live in. Many philosophers now think there is no use in talking to skeptics—that no argument can change their minds, thereby curing them of their skepticism. These philosophers opt for a merely preventive response, aiming to convince only non-skeptics that they can resist skeptical arguments. I argue that a cure is necessary, viable, and theoretically illuminating.

First, I argue that the merely preventive response must fail. To succeed with it, I explain, we would have to understand why skeptical arguments appear compelling. We would then find out either why the arguments seem compelling, but are ultimately not, or that they are indeed compelling. In the first case, a cure would be within reach; we could explain the skeptic’s error to her. In the second, prevention would come too late; we ourselves would need a cure. It follows, I argue, that until we can show a skeptic how she has gone wrong, we cannot resist her arguments in good faith.

Second, I argue that we can in fact change a skeptic’s mind. I begin by considering influential arguments for skepticism about the external world, including the argument from closure and the classic argument formulated in Jim Pryor’s “The Skeptic and the Dogmatist.” I show that, despite apparent differences, all these arguments rely on a shared, tacit premise: that perception never puts us in touch with the world in a way that guarantees that things are as we seem to perceive them to be. I then argue that the best arguments for this shared premise are question-begging. This suggests that the premise is a groundless intuition, and thus that external world skepticism lacks any solid foundation. Showing this to the skeptic clears the obstacles to her accepting, on ordinary grounds, a view on which perception can straightforwardly provide us with knowledge of how things are around us. This acceptance cures the skeptic.

Third, I argue that my ambitious, curative response can help us understand the nature, significance and history of skepticism. For Hume, I explain, skepticism is primarily a temperament. As he understood it, a skeptical temperament leads to excessive questioning and even madness when overly dominant, but only carefulness and rigor when balanced with other temperaments. Tracing skepticism to a groundless intuition helps motivate Hume’s focus on temperaments and feelings. Hume’s conception of proper temperamental balance, in turn, helps us grasp the skeptic’s nature, how to diagnose skepticism, and what we can learn from the skeptic even as we cure her.

The curative response also helps us understand Kant’s views, and vice versa. Standard readings of Kant portray the central arguments of his first Critique as meant in part to expose contradictions within skeptical empiricism. On my reading, Kant’s attitude toward the skeptical empiricist is not so adversarial. Instead of refuting the skeptic, he offers her an alternative conception of the mind and its relation to the objects of knowledge—one which makes sense of our knowing much of what such a skeptic doubts. Though this conception can seem at odds with skeptical empiricism, I argue that Kant is right to expect that the skeptic would find it appealing. Kant’s portrayal of skepticism as arising out of a despair of understanding human knowledge explains why, and teaches a general lesson about how to cure skepticism: Offering the skeptic a viewpoint which makes sense of our knowledge allows her to overcome the frustration from which her skepticism first arises.

If I am right, we can and should talk to skeptics. We need not be quiet or dogmatic in their presence. We can show them the groundlessness of their views, instead of conceding the groundlessness of ours. And we can change their minds by offering a compelling, alternative conception of ourselves.